The labor market is back to normal. Or so we are told. Here's the prime-age unemployment rate for the United States beginning in 1960.

This is already a long post, so I don't really have space to ponder the question of Whither Human Labor? It seems likely that an increasing number of tasks presently labeled non-routine will become routine (still lot's of room in manufacturing it seems, see here). We have seen this with robo-advisors in the financial sector and the emergence of artificially-intelligent doctor apps (see here) among many other places. How might the future unfold? Here's one take, by Andrew McAfee: Are Droids Taking Our Jobs?

Above we see the familiar cyclical asymmetry, in which the unemployment rate spikes up sharply at the onset of a recession and declines gradually during the recovery. As of today, the prime-age unemployment rate is at 4%, close to its recent historical norm.

Other measures of labor market activity, however, tell a slightly different story. Here is the prime-age employment-to-population ratio. Employment took a big tumble during the recession--especially for males--and its taken a lot longer to recover than unemployment. In fact, we're not quite back to pre-recession average of about 80%.

The reason employment has recovered more slowly than unemployment is because significant numbers of prime-age workers left the labor force in the aftermath of the Great Recession. This pattern has reversed only recently.

By these standard measures of aggregate labor market activity, the U.S. labor market appears close to "full employment." Nevertheless, there is still much anxiety concerning the present state and future course of the U.S. labor market. Much of this anxiety stems from the perennial concerns regarding the impact of international trade and technology on future employment opportunities.

To assess the nature of these concerns, we have to move beyond the standard aggregate measures of labor market activity, which have remained relatively stable since 1990 in the face of growing trade deficits and technological progress. So if trade and technology are going to have an impact on employment opportunities, it's likely going to happen at the sectoral and/or occupational level.

Of course, a changing allocation of human labor across sectors of the U.S. economy is nothing new. Here is the share of employment in agriculture and manufacturing since 1815.

In 1815, 80% of employment was devoted toward the production of food. And for those of us who have never worked on a farm, here's how Charles H. Smith describes the venture in 1892:

“It’s about the meanest business I have ever experienced. It’s all fact—solemn fact – no romance, no poetry, no joke. It does seem to me that all this sort of work ought to be done by machinery or not to be done at all.” Source: Farm Life at the Turn of the Century.

As we can see, Smith got his wish. Over the centuries, machines have replaced most of human labor in the production of food. Was this a welcome development? Most of us today would likely answer in the affirmative. However, sectoral transformations like this also come at a cost, borne by those who are compelled to do the adjusting. A shovel that helps ease a manual burden is one thing. A combine harvester that renders a certain kind of labor redundant is another. When the demand for a certain type of labor in a given sector is diminished, what are workers to do?

One thing they can do is employ their labor in the production of the machines that replaced their labor on the farm. And so youngsters left the family farm and immigrants flowed increasingly into the communities that offered employment in manufacturing and other sectors. I'm not sure how much of an improvement it was to substitute the drudgery of farm work with the drudgery of factory work, but it was probably an improvement in net terms (however small). The relatively high levels of comfort most Americans enjoy today did not come about until the latter half of the 20th century. And by that time, manufacturing employment (as a share of total employment) began its long secular decline.

So, what accounts for the decline in manufacturing sector employment? According to Dean Baker, the U.S. trade deficit has a lot to do with it.

Since 2000, employment in the U.S. manufacturing sector has dropped from about 17 million to 12 million workers. The sharp decline started with the "China shock" in 2001 (also a recession year). On the other hand, Germany has also experienced a decline in manufacturing sector employment while running trade surpluses. Arguably, the trade surpluses muted the secular decline in manufacturing employment in Germany, while the U.S. trade deficits exacerbated the process of structural readjustment. The trade deficit has almost surely had some impact on U.S. manufacturing employment, but it's hard for me to escape the conclusion that most of the sectoral reallocation of labor has been driven by technology. The next diagram tells the story.

But it hardly matters to an individual worker whether they are displaced by a foreigner or an automaton. Where are the new jobs to be found and what are they paying? Are all of our good, high-paying manufacturing jobs being replaced by lousy low-paying service sector jobs? There is an element of truth to this. As Daniel Alpert points out, since the cyclical peak in 2007, the U.S. economy has added close to 7 million jobs. About 60% of these jobs appeared in the "low-wage, low-hours" sectors that account for about 36% of all private sector jobs; see table below.

The picture is not quite as bleak as Alpert paints it. Andrew Spewak (my trusty RA) took it upon himself to produce this table.

What this decomposition shows is that there is in fact substantial net job creation in high-wage/high-hour jobs in the service sector. The bleakness is heavily concentrated in manufacturing (which we know is in secular decline) and in construction (which is not in secular decline, but which hit a peak just prior to the housing crisis).

Let's dig a little deeper and explore the task-based view of the labor market developed by Daron Acemoglu and David Autor (see here). According to this view, goods and services are produced by a set of tasks that can be performed by various inputs, like capital and labor. Tasks differ along two important dimensions. The first dimension measures the relative importance of "brains v. brawn" in performing a task. This is labeled "manual" v. "cognitive" in their analysis. The second dimension measures the extent to which a task can be described by a set of well-defined instructions and procedures. If it is, then it is possible to have an automaton execute a program to perform the task. Acemoglu and Autor label these "routine" tasks. If instead the job requires flexibility, creativity, on-the-fly problem-solving, or human interaction skills, the occupation is labeled "non-routine."

Here's how some broad occupational classes fall into the four implied categories:

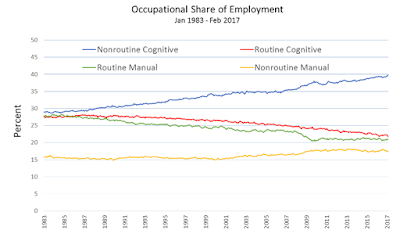

Of course, no classification scheme is perfect, but you get the idea. And here's how the employment shares for each category behave since 1983:

This graph could be labeled "The Decline of Routine Work." We have seen how the machines have substituted for manual labor. Robots are increasingly doing the same thing for many cognitive tasks. Here's a male/female breakdown of the phenomenon:

The decline of routine labor has been associated with "polarization"--that is, a "hollowing out" of America's middle class. This is because routine jobs, whether manual or cognitive, generally pay "middle class" wages.

The share of employment allocated to these middle class jobs is declining. Where is this middle class going? Largely to jobs in higher wage category, associated with non-routine/cognitive occupations. But there's also a moderate increase in the share of employment in the lowest wage category, in those jobs associated with non-routine/manual occupations.

0 nhận xét:

Đăng nhận xét